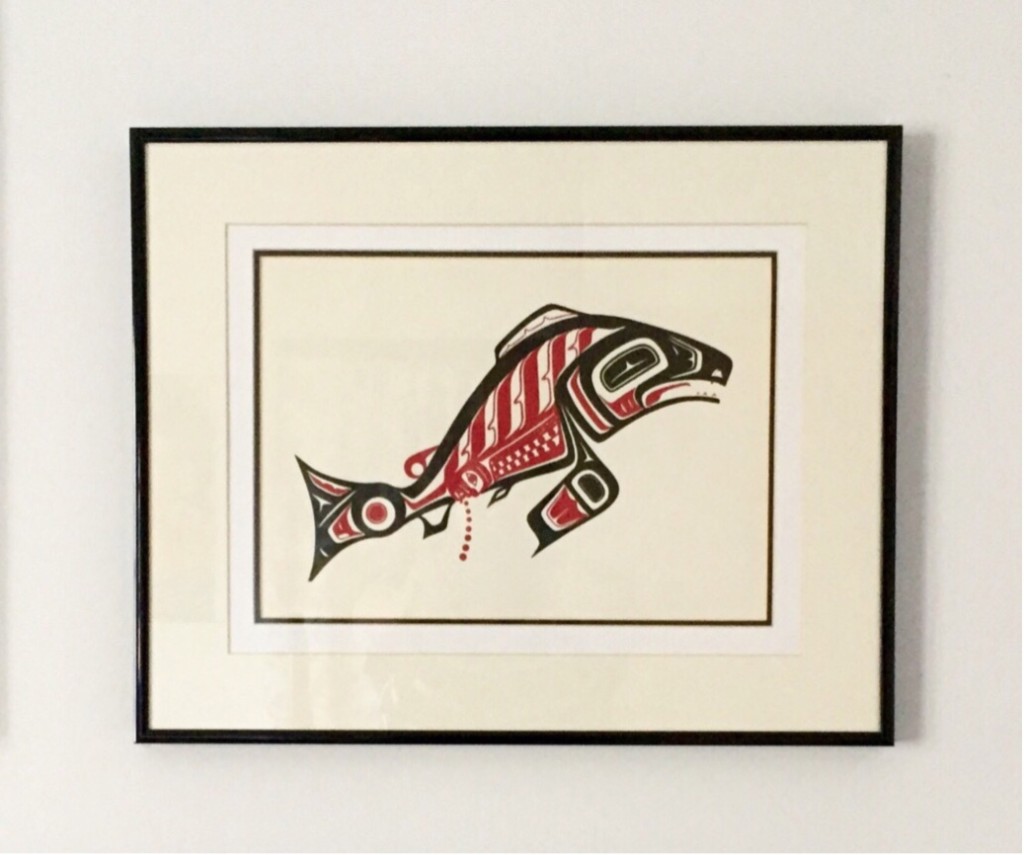

The greatest part of moving to St. Paul thus far has been the sheer amount of local antique and thrift shops. I love antiquing because of the treasures you unexpectedly come across. A while ago, I posted about two Ainu nipopo dolls that I stumbled across in an Orange County shop. Although I will never again be so lucky, it is surprisingly easy to find affordable and original artwork when antiquing. Although I am usually pretty lucky with American prints and lithographs, this past weekend I spotted an Inuit painting of a salmon hung high on the wall. Needless to say, about an hour later, it came home with me.

Salmon was and is a lifeline for many northern indigenous peoples, the Ainu included. In Hokkaido, Ainu elders hold ceremonies for the divine fish (kamuy cep) to ensure their abundance each year. The fish held importance as both spirit and sustenance. (If you want to know more about the relationship between the Ainu and salmon, especially now, I recommend this essay). It is amazing how the stories of the salmon in the Pacific Northwest resonate with those of the Ainu. Recounted by Clint Leung, the salmon were seen as eternal people who lived in the ocean. When the tribes who lived on land were starving, the salmon presented themselves as fish to ease their hunger. The bones of the salmon were ceremonially taken back to the ocean in order to ensure their return the following year. Animals that give themselves to satiate our hunger are worthy of our respect.

In 2010, the Inuit Gallery of Vancouver held a show called The Return: Salmon Imagery in Northwest Coast Art. The artists blended traditional designs and iconography with their own signature style and materials in sculpture, painting, and jewelry design. The “return” in the title could refer to the yearly return of the spawning salmon to the river or the original return of the salmon’s bones to the ocean. But it could also refer to a return of interest in a fish that has been heavily impacted by everything from industrialization, over fishing, pollution, to climate change. As various species dwindle, people are once again considering the cultural and environmental importance of the fish. The website for exhibition shares a quote from Andy Everson, who explains, “People often ask me why I keep including salmon in my artwork. The answer to this lies with the importance of salmon to me, my relatives and my ancestors. Put simply, salmon was the vital link between mere survival and the development of the splendor of our culture.”

One thing about looking at art from the Haida, Tlingit, Tsimshiam, Kwagiutl and Sadish peoples in the Pacific Northwest is that there is a certain inventiveness and consistency of design that makes the styles iconic. I agree with Leung in that if you put works from this region next to any other, you would still be able to isolate those features which make it unique. Although his e-book on Pacific Northwest art focuses on sculpture and falls short of an academic treatise, it provides a helpful cheat sheet for beginners introducing some of these design elements–the formline, the ovoid shape, the u-form shape, the split u-form shape, and the s-form shape. These small elements are combined, juxtaposed, and contrasted to create larger forms. Most all of these shapes can be found in Lyle Wilson’s The Trapped Salmon above, but they are also present in the painting that I found.

In this work, the formline of the salmon is a thick and black modulated line that encases most of the body. Although most contemporary artists use commercial ink, in traditional works, the formline was typically created with pigment from charcoal, graphite or lignite charcoal. Occasionally red formlines are also seen, created from red ochre or hematite. Several ovoid shapes make their appearance here. It defines the eye socket of the salmon, fills out the fin, and is used to hinge together the body and the tail. The body of the salmon is defined by contrasting s-form shapes, which mimic the striation of the salmon’s flesh, and split u-form shapes perhaps reminding us of its bone structure. The split u-form shape reappears inside the eye, fin, and tail. And, finally, the fish’s gills are defined by a single, simple u-form shape. The aspect of this work that interests me is the string of pearly red roe spewed almost fountain-like out of the mouth of a face located near the fish’s pelvis.

All of these small shapes merge together to form a larger creature. Alongside the salmon, artworks commonly feature the bear, the killer whale, the thunderbird, and the raven. The repetition of common forms across these sacred creatures is a powerful device in both traditional and contemporary art. I also find that art from the Pacific Northwest presents a great opportunity for teaching students visual analysis, and the differences between iconography and style, or about the different effects of line, space, and color.

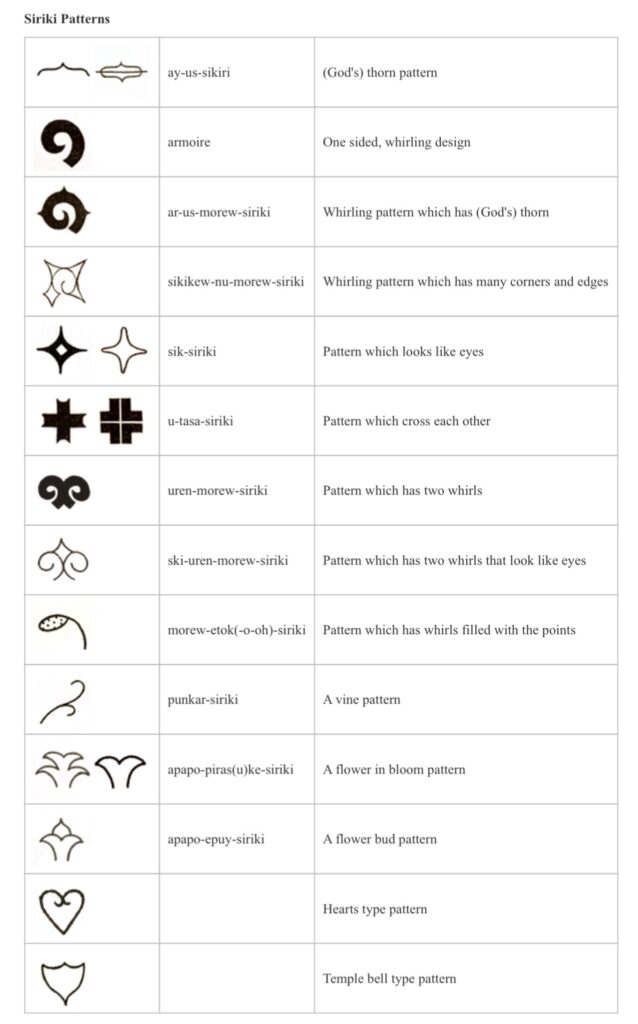

In my own research on the Ainu, it is not all that common to see representational art in older work (although bear carving and representations of salmon are both present staples of tourist and contemporary art). Instead, most graphic art similarly focuses on the repetition of smaller design elements, called siriki in Ainu. In embroidery and woodcarving, these patterns are combined into unique compositions, as seen here in these Ainu robes. I’ve reproduced a helpful chart from the Ainu Pirka Kotan website for your reference below. Occasionally there is more in common than what appears at first glance.

In my own research on the Ainu, it is not all that common to see representational art in older work (although bear carving and representations of salmon are both present staples of tourist and contemporary art). Instead, most graphic art similarly focuses on the repetition of smaller design elements, called siriki in Ainu. In embroidery and woodcarving, these patterns are combined into unique compositions, as seen here in these Ainu robes. I’ve reproduced a helpful chart from the Ainu Pirka Kotan website for your reference below. Occasionally there is more in common than what appears at first glance.

If anybody knows any information about the artist of this work (or helpful resources that may point me in the right direction), please do let me know. I would love to learn more about it.