- Date: January 1, 2016

Takashina, Erika. “Sea of Hybridization: In Dispute over Urashima” from The Sea Beyond: Hōsui, Seiki, Tenshin, and the West. Translated by Christina M. Spiker. Review of Japanese Culture and Society 26:1 (2014), 80-103.

ABSTRACT

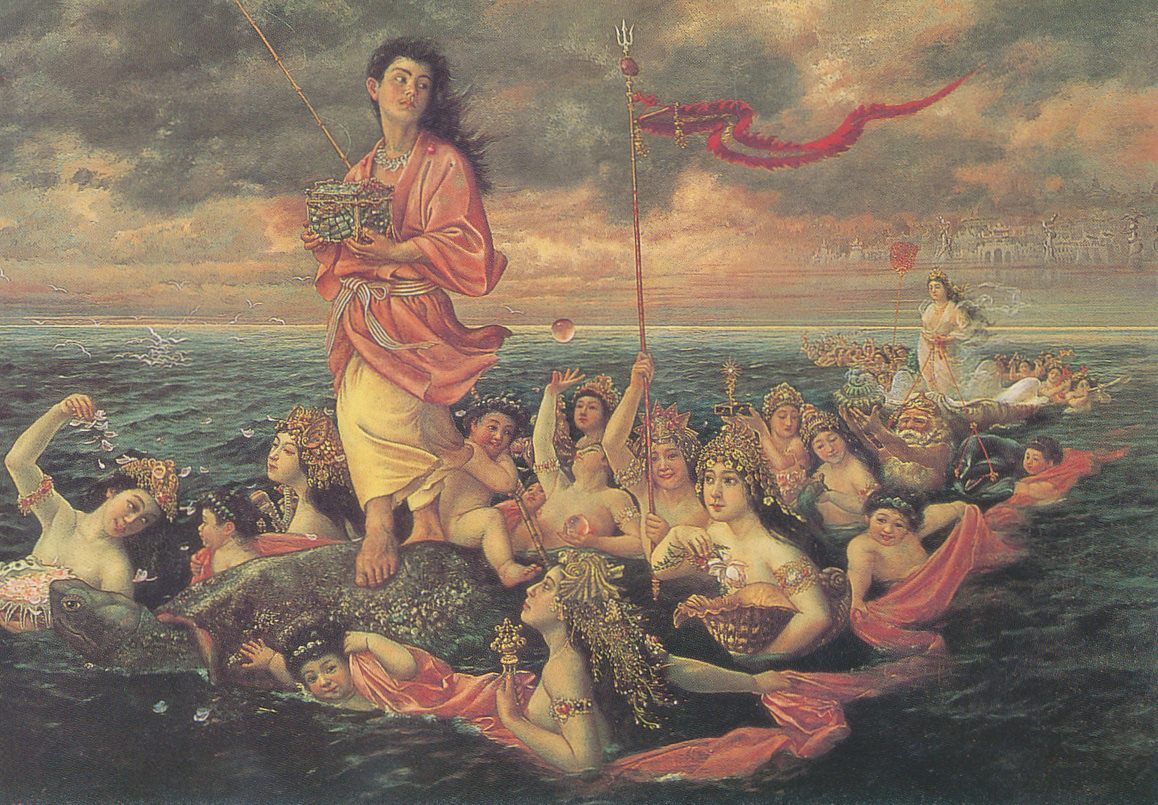

The selection here has been excerpted from the third chapter of Takashina Erika’s book The Sea Beyond: Hōsui, Seiki, Tenshin, and the West (Ikai no umi: Hōsui, Seiki, Tenshin ni okeru seiyō, 2000). Her iconographic approach to the works of the influential Meijiperiod oil painter Yamamoto Hōsui (1850–1906) charts the oscillation between Japan and the West in one of the more tumultuous moments in modern history. The narrative of Japanese art influencing French and other European artists is well known, but less known is how an aspect of European art history unfolds through Yamamoto’s life. The study begins with the discovery of drawings he realized on the interior walls of his friend Judith Gautier’s summer home in Brittany, France. Taking this little known work and a group of watercolors that Yamamoto painted for a literary journal in France that was born out of a transcultural friendship as her starting point, Takashina locates and tracks the artist’s footprints during his Paris years, showing how he fashioned himself into a practitioner of the Western tradition while feeding an appetite for Japonisme among his European companions. In Chapters One and Two, the author sheds light on the works Yamamoto produced in France, many of which are discussed for the first time in The Sea Beyond. Chapter Three assiduously combs through the ingredients of Yamamoto’s masterpiece, Urashima (1893–95), produced after his return to Japan, by placing the work in a subtle yet unceasing oscillation between Japan and Paris, the two places Yamamoto held dear to his heart. Among the signs inscribed onto the canvas is a series of double articulations that binds his native and adopted homes, the local debates that sought to advance an essentialist view of Japan, and the travails of international politics. In Chapter Four, he sets sail to Okinawa, a site of Japanese coloniality; and in Chapter Five, the artist works on zodiac paintings that further mobilized the duality and hybridity of his shifting environment and tradition. The final chapter of the book examines how the painter Kuroda Seiki grappled with Okakura Tenshin’s legacy of institutionalizing Nihonga (Japanese painting) in seeking to resuscitate Yōga (Western oil painting) in Japan.

Takashina draws out two forms of transnationalism in Yamamoto’s work and his encounters abroad: geopolitical struggles among nation-states and personal ties among artists. The iconographic layers of Urashima bring to surface the relationship between Yamamoto and the West that almost reads like an encrypted message sent across the ocean to circumvent national divisions and warfare. In that duality–or duplicity, perhaps–the possibility of a genuine friendship is charted as one poetic force of the piece. The image is studded with Japanese motifs specific to the intellectual current of that particular period, yet the very compositional arrangement traces the thoughts and sights he encountered in Paris. These hybridizing moments in his art are less about the inevitable political course that modern Japan had to take than the cosmopolitan promise proposed by the foreign other. Beneath the factual events that bound the fate of multiple nations together in war and politics, suggests Takashina, an equally powerful art world was also forming to help make sense of modernity. And painting was an effective tool to articulate difference and posit a coherent imagination, not just for the Japanese but also for the French who, it seems, needed Yamamoto’s very presence to conceptualize their modern experience. Modern art, inThe Sea Beyond, is a record of intercessory nautical movements that constantly drew toward and pulled away from whatever “origin” modernity sought to identify, all the while positing, instead, intimacy and meaning in the processual global drift.

(Kenichi Yoshida)