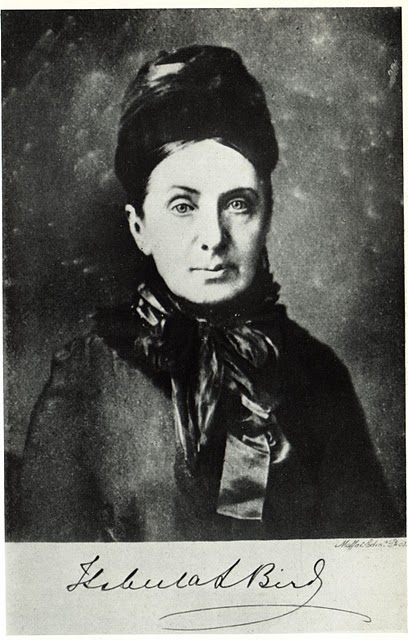

Today I went with two friends to see the exhibition “イサベラ・バードの旅の世界―ツイン・タイム・トラベル” (In the Footsteps of Isabella Bird: Adventures in Twin Time Travel). The exhibition featured photographs taken by Japanese professor of geography, Kanasaka Kiyonori (金坂清則, University of Kyoto) over the course of 10 years following the footsteps of Victorian explorer Isabella Bird. This traveling exhibition has now been to several locations along Bird’s route around the world including the National Library of Scotland (2005), The Oriental Club (London, 2008), University of Dundee (2008, Australia), the Hawai’i State Library (2011, USA), and recently, The Hokkaido University Museum (2014, Japan).

Today I went with two friends to see the exhibition “イサベラ・バードの旅の世界―ツイン・タイム・トラベル” (In the Footsteps of Isabella Bird: Adventures in Twin Time Travel). The exhibition featured photographs taken by Japanese professor of geography, Kanasaka Kiyonori (金坂清則, University of Kyoto) over the course of 10 years following the footsteps of Victorian explorer Isabella Bird. This traveling exhibition has now been to several locations along Bird’s route around the world including the National Library of Scotland (2005), The Oriental Club (London, 2008), University of Dundee (2008, Australia), the Hawai’i State Library (2011, USA), and recently, The Hokkaido University Museum (2014, Japan).

According to a press release in the Japan Times (2006), Kanasaka has translated several of Birds’ travel works into Japanese and adopts the concept of “twin time travel” as a methodology that allows him to visit sites from a century earlier and examine lines of continuity or change in the landscape and urban structure. According to that article, although geographers typically do not focus on a single person as the basis for the research, Bird’s exploits formed an interesting microcosmic study. Her vivid descriptions of distant locales are certainly compelling, even today, and Kanasaka explains that Bird’s work serves doubly as both travel writing and historical document.

The exhibition was divided into two sections on the 1st and 3rd floors (divided by a melange of exhibits about everything from paleontology to wax models of skin diseases). The contemporary and nineteenth-century photos/illustrations were stacked vertically, with Kanasaka’s photographs usually taking the top register. A small plaque accompanied each set of works containing the title of the work, the book in which it was found, and then a small quotation from the relevant book in both English and Japanese. Following the prescribed route between the rooms, one could easily see the transition between the illustrated volumes in the beginning, and Bird’s own photography towards the end, but there wasn’t much in the way of commentary. The third floor also displayed some of Bird’s original books behind glass, and Japanese translations available to read. One corner focused on the exhibition history of the show, posting various press releases from around the world.

The exhibition was divided into two sections on the 1st and 3rd floors (divided by a melange of exhibits about everything from paleontology to wax models of skin diseases). The contemporary and nineteenth-century photos/illustrations were stacked vertically, with Kanasaka’s photographs usually taking the top register. A small plaque accompanied each set of works containing the title of the work, the book in which it was found, and then a small quotation from the relevant book in both English and Japanese. Following the prescribed route between the rooms, one could easily see the transition between the illustrated volumes in the beginning, and Bird’s own photography towards the end, but there wasn’t much in the way of commentary. The third floor also displayed some of Bird’s original books behind glass, and Japanese translations available to read. One corner focused on the exhibition history of the show, posting various press releases from around the world.

My own feeling wandering around the exhibition space was that this was a story of Kanasaka’s adventure more than that of Bird. While the photographs do cause us to think about issues of mutability and continuity in the physical landscape, the element that felt missing in this exhibition was a nod towards the robust world that Bird herself cited from. And when thought of in this way, Bird herself becomes a vehicle for the contemporary traveler.

Japan. Photo by

Kanasaka Kiyonori.

However, perhaps scholars do “twin time travel” all the time in their own work without even realizing it. In my own case, after locating nineteenth-century photographs taken by Arnold Genthe, my curiosity couldn’t sway me visiting the towns he also visited in Hokkaido. But Genthe himself may have modeled some of his own photographs taken in 1908 on the illustrations of A.H. Savage Landor published in 1893, who in turn, had an eye on Isabella Bird’s Unbeaten Tracks of 1880. In that sense, although the way that the photographs are presented in the exhibition invites a one-to-one comparison, perhaps a more productive way to view them is as new additions to a diverse and long-standing economy of tourist images. When looked at from that perspective, perhaps the real question we should be asking is not about change, but the continuity of the “view”? Despite changes in technology and landscape, why do we seek to recapture a certain nostalgic “sameness” in our travel photogrpahs?